Here's How On-Field Player Tracking Tech Works

Going back over a quarter-century, sensors allowing for the tracking of player and equipment data have been a staple of sports broadcasts on television. At one point, it was as simple as making hockey pucks easier to see on Fox's NHL broadcasts by making the puck glow for TV viewers, but in time, it's grown to all sorts of stat collection, used to enhance both TV broadcasts and teams' analytics departments.

As technology has advanced, particularly with the advent of small RFID chips that can transmit player data, the ease of accessing massive cloud computing resources from companies like Google and Amazon, and specialized cameras, there are many ways that both players and game balls/pucks/equipment can be tracked.

The process has evolved over the years and varies by sport, but it's become part of all of the major leagues. Based on what the various leagues and technology providers have made public in the media, let's look at some of the tech that has previously been and is being used to provide better insight into professional athletic performance.

FoxTrax illuminated hockey puck

Sensors in sports as we know them can be traced back to 1996's introduction of the FoxTrax illuminated hockey puck, an augmented reality enhancement that made it easier to see the puck on TV. When Mediaweek first reported on the development of the puck in June 1995, Fox Sports' then-president David Hill wouldn't confirm or deny the story, albeit while conceding that Fox was working on something. "[We are] looking at every opportunity possible to enhance the viewing of the game through technological innovations," he said. "People at the networks have tried this sort of innovation before, but the technology of trying what is now being rumored is extremely complex."

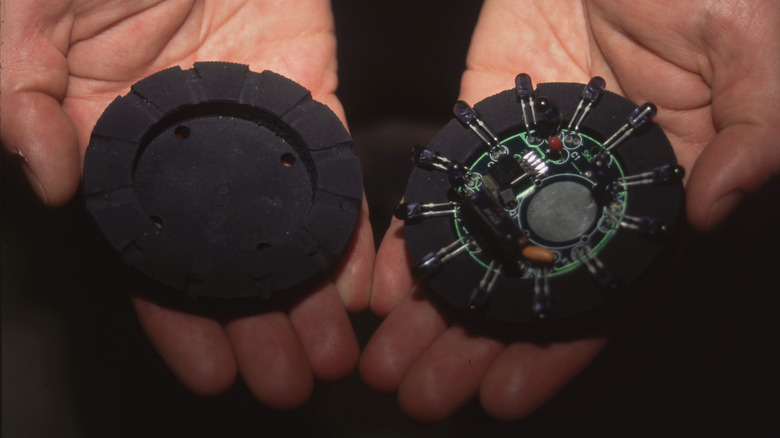

It was real, though: A puck that glowed blue on TV and picked up a red trail behind it at high speeds. Shortly after FoxTrax debuted, a May 1996 Popular Mechanics article broke down how it worked: A standard puck was cut in half, hollowed out, fitted with a "circuit board about the size of a silver dollar," and outfitted with 20 infrared emitters.

This was augmented by sensors placed above and around the rink to determine the puck's speed and position, while four Silicon Graphics workstations in the production truck were tasked with handling the actual visual effects. A complicating factor was the battery technology of the time, as each FoxTrax puck could only run for 10 minutes, requiring Fox to bring 50 of them for its debut at the 1996 NHL All-Star Game.

Watching FoxTrax in action today, it doesn't read as particularly obtrusive but was largely criticized by sports media at the time, and subsequently, it was ditched before the NHL package's 1998 move to ABC.

Modern hockey puck and player tracking

Sportvision, the company that developed FoxTrax, eventually returned to hockey, but it took some time, with the NHL experimenting with the newer technology during the 2015 All-Star Weekend.

"These are competitive, repeatable situations where we're going to take a hard look at the system, a hard look at the data that comes off of it, and really understand at a scalable level what it means to deploy this night after night after night, multiple times a day in this situation," NHL's then-executive vice president of digital media and strategic planning Steve McArdle told NHL.com in August 2016. The new system involved 10 infrared cameras on the arena catwalk to capture what the puck's infrared emitters sent out while also gathering data transmitted by chip-based trackers in the puck and the players' jerseys that were designed with the idea of providing additional data for the TV broadcast.

"This is not the glowing puck," NHL's then-COO John Collins told USA Today in January 2015. "That is not the intended use of this technology." Several weeks later, he elaborated to Sports Video Group that, for contact sports, chip-based systems, like the one the NHL was adopting from SportsVision, were superior to camera-based systems like the old FoxTrax.

Sportvision's then-CEO Hank Adams added that while the system provided valuable analytics, there still needed to be a layer of human intervention. "When we get into who's in possession of the puck, that has to be a human involved in it because we don't have electronics on the sticks," said Adams in the same USA Today article. "There's only so much you can really use this stuff to replace. A human being is going to have to get involved at a certain point and make these judgment calls."

Golf ball tracking

In the golf world, play is tracked using TopTracer, which previously went by the name ProTracer until it was purchased by TopGolf in 2016. According to TopTracer, the technology has its roots in Swedish native Daniel Forsgren becoming frustrated by how hard to follow a 1998 golf broadcast was. Making it his mission to develop a camera that could track the ball's movement and make it easier to see on TV, he eventually quit his day job in the IT sector in 1998 to work on his idea full-time. By 2006, he had a viable product, and TV networks quickly adopted it.

According to the golf website Par3NearMe.com, TopTracer uses complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) sensors in the camera with the idea of capturing a three-dimensional space and the ball's movements within that space. The data from the TopTracer is fed into a computer that collects the tracking data and generates the ball-tracking graphics that are used to augment the TV broadcasts. The technology proved so popular that it expanded beyond the TV production space, with a version intended for use by driving ranges introduced in 2012. It's still a staple of TV golf coverage, though, serving as the PGA's "official range technology."

NFL Next Gen Stats

The money machine that is the NFL is, unsurprisingly, at the forefront of player-tracking technology, which the league uses to fuel its Next Gen Stats platform. According to the NFL, its tracking system consists of "20–30" ultra-wideband receivers, "two-three" RFID tags that are integrated into each player's shoulder pads, and additional RFID tags that are placed "on officials, pylons, sticks, chains, and in the ball."

Roughly 250 trackers are working during every NFL game, and at a rate of 10 times per second, they record data on speed, acceleration, location, and distance traveled. Using machine learning running on Amazon Web Services, coaches and broadcasters get stats generated by the trackers, borrowing from "[m]ore than 200 new data points ... created on every play of every game." The advanced analytics produced by all of this include predicting completion probability, expected rushing yards, and win probability.

"Eight to 10 years ago, none of us would have thought miles-per-hour was going to be a metric of any consideration in American football," John Pollard, then-VP of business development for Zebra Technologies, the NFL's RFID tech provider, told CBS Sports in June 2021. "Within the last two to three years, all the broadcast partners have become much more comfortable and fluent in the tracking data and leveraging it in the process of providing new dimensions to storytelling in a game."

Asked if the technology could get to the point that it could dictate ball location with the necessary accuracy, Matt Swensson, the NFL's VP of emerging products and technology, added that such technology wasn't quite ready yet. More specifically, he said that getting there would necessitate "a combination of optical and camera-based feeds with tracking data," followed by "getting to a precision level that we're comfortable with."

MLB pitch tracking

Pitch tracking is a key part of Major League Baseball's Statcast system, and according to a November 2023 Sports Illustrated article, it was upgraded for the 2023 season. Previously, there were five cameras, each running at 100 frames per second tracking pitches, compared to seven cameras — each running at 50 frames per second — tracking players and hit pitches. For the 2023–24 season, the five pitch-tracking cameras — two behind home plate and one each at first base, second base, and in center field — were upgraded to 300 frames per second to capture the relevant data with higher accuracy.

The biggest reason for tripling the frame rate was to attempt to better capture the moment when the ball arrives at home plate and is either hit or missed by the batter. Even at 100 frames per second, a 90 to 100 mph pitch traveling 60.5 feet moves so quickly that the key moment could easily take place between captured frames.

The Sports Illustrated article adds that "the data is transmitted even faster than the pitch itself," with the camera communicating the ball coordinates along with every single frame. "It's automated to the degree that in 250 milliseconds after that pitch is released, when it's on its way to the plate, we know how fast that was, and we can send it to the scoreboard," noted Ben Jedlovec, MLB's senior director of baseball data platform product. That's how the graphics showing pitch type and speed show up seemingly instantaneously because all of that is calculated in real-time on Google Cloud.