Why California's Right To Repair Law Could Have Big Implications For The US

While requests for personal mechanical and device repair have been around for decades, the "Right to Repair” movement really started in earnest in 2012. That was when the first Right to Repair law was passed in Massachusetts for automotive repair.

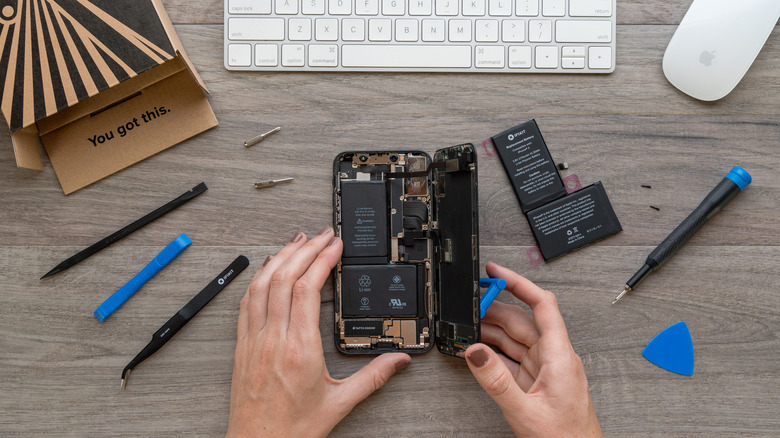

Since then, the focus of the movement has mostly shifted toward personal electronics like smartphones. Phones can break after just a few years of use, and often can't be repaired under a user's own power due to a lack of parts and instructions. Today, the Right to Repair movement has taken a major step forward thanks to the passage of a new law in California.

The California state government, headed up by Governor Gavin Newsom, passed a new statewide Right to Repair law today — four years after the bill's initial introduction back in 2019. According to this new law, there are stipulations for various kinds of tech depending on their cost: Any electronic device that costs between $50 and $99 must be fully supported by its creators for at least three years, including offering replacement parts and repair documentation. For devices that cost $100 or more, support must be offered for seven years.

Any companies that fail to comply with this law will be subject to fines of thousands of dollars for every day support remains unavailable. The law will officially go into effect starting on July 1, 2024.

Rippling effects for the tech industry

With the success of the California bill, a precedent has now been set for the western electronics industry as a whole, as both state and federal governments begin weighing further Right to Repair measures. California does have a habit of setting precedents for the rest of the country with its passage of marijuana legalization and emissions standards laws. In an ideal scenario, we could see these kinds of consumer protections cropping up all over the United States.

Even if they don't, electronics manufacturers could start offering replacement parts and documentation outside of California just to prevent any troublesome issues from cropping up, not to mention the potential of third-party component circulation. After all, companies can charge for parts they distribute, as opposed to individual consumers circulating parts themselves.

Of course, this is only in the best case scenario. At the moment, California's new law only applies to simple consumer devices like smartphones, while larger devices like game consoles, industrial equipment, or home security systems still remain unprotected. With any luck, though, this newly-set precedent will both encourage companies to be more forthcoming with support, as well as help to conserve the resources used to create new phones.